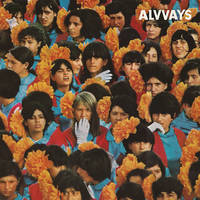

Yes, it’s “Alvvays” as in “always,” not “All-vays”—but that typographic quirk is more than just an opportunistic ploy for this Toronto quintet to enhance its search engine optimization. (If anything, Alvvays’ dual affinities for post-C86 girl-group revisionism and dusty-grooved distortion strongly suggest they’re yearning for a time when seeking out bands involved trans-Atlantic fanzine correspondence and mail-order forms.) Apparently, the curious spelling was implemented to avoid confusion with the bygone, like-minded British indie-pop outfit with the same name. However, Alvvays actually proves to be a perfect visual manifestation of this band’s thematic framework: with nearly every crestfallen song on their debut pitched at the crossroads of commitment and abandonment, nostalgia and uncertainty, the band’s name effectively becomes the textual representation of the broken promises catalogued within.

Yes, it’s “Alvvays” as in “always,” not “All-vays”—but that typographic quirk is more than just an opportunistic ploy for this Toronto quintet to enhance its search engine optimization. (If anything, Alvvays’ dual affinities for post-C86 girl-group revisionism and dusty-grooved distortion strongly suggest they’re yearning for a time when seeking out bands involved trans-Atlantic fanzine correspondence and mail-order forms.) Apparently, the curious spelling was implemented to avoid confusion with the bygone, like-minded British indie-pop outfit with the same name. However, Alvvays actually proves to be a perfect visual manifestation of this band’s thematic framework: with nearly every crestfallen song on their debut pitched at the crossroads of commitment and abandonment, nostalgia and uncertainty, the band’s name effectively becomes the textual representation of the broken promises catalogued within.Such quarterlife-crisis concerns—the bane a generation that, as one song puts it, feels like it’s “too late to go out, too young to stay in”—are natural preoccupations for a band of twentysomethings that is the very product of upheaval and a clean-slate reset. As recently as two years ago, Nova Scotia native Molly Rankin was still trying to establish her identity as a solo artist on the maritime club circuit—a task made all the more formidable by the fact she’s a descendent of Canadian roots-music dynasty the Rankin Family. An EP released under her own name in 2010 suggested she was destined to travel down a similarly bucolic path, casting her cheekily self-deprecating lyrics and siren of a voice in familiarly folksy surroundings. However, her partnership with that record’s guitarist Alec O’Hanley (formerly of Prince Edward Island power-popsters Two Hours Traffic) would eventually turn more ambitious. With Rankin enlisting childhood friend Kerri MacLellan on keyboards and O’Hanley recruiting PEI pals Brian Murphy and Phil MacIssac on bass and drums, the quintet relocated to Toronto last year with their new name, new aesthetic, and, in former brunette Rankin’s case, new hair.

But it's not just the singer’s striking, peroxide-blond locks that make Alvvays stick out from the infinite number of contemporary indie acts forging a similar union between early-’60s AM-radio pop and late-’80s freak-scene discord. On the band’s winsome Chad VanGaalen-produced debut, it’s the disarmingly frank, aching lyricism that ultimately raises them above the cardiganed fray, capturing both the humour and heartache of seeking intimacy in the big city. Amid the buoyant surf-tingled jangle of the opening “Adult Diversion,” Rankin isn’t just discreetly ogling a fellow commuter from afar; she’s already plotting out their future domestic bliss, asking her oblivious object of desire, “How do I grow old with you even if you don’t notice as I pass by you on the subway?” The rousing, pints-aloft follow-up, “Archie, Marry Me”, serves as a sequel of sorts where Rankin has got the guy, but not the ring—and yet she already sounds less like she’s fighting for the love of her life than checking items off a list (“Honey, take me by the hand, and we can sign some papers/ Forget the invitations, floral arrangements, and breadmakers”), thereby proving that the only thing more tragic than a break-up song is one about a person desperate to break in.

Rankin possesses the sort of radiant but deceptively deadpan voice that lets her to infuse these lovelorn laments with sly, sometimes sinister wit: when she sings, “I left my love in the river” on the drowned-boyfriend requiem “Next of Kin”, there’s the simmering implication that she could’ve done a little more to save him. (The chorus to the dreamy slow-motorik ballad “Ones Who Love You,” meanwhile, is home to the most beautifully nonchalant f-bomb.) This sense of irreverence bleeds into the album’s production, whose scabrous guitar lines, synth-blurred vistas, and drum-machine experiments reveal the band are hardly the purists their pedigree might indicate. Presenting a brighter contrast to the claustrophobic insularity heard on VanGaalen's own recordings and in his work with the much-missed Women, Alvvays eagerly scuffs up the band’s gold sounds with dissonant edges—not to deliberately obscure the gleaming melodies or make the band seem tougher than they are, but to enhance the very feeling of raw-nerved unrest seeping through Rankin’s lyric sheet. This is the sound of pristine pop music blasted through cheap, blown-out headphones—and every time it seems like a song is about to decay before your ears, you sense both the sadness and liberation of knowing that nothing lasts forever. Reported by Pitchfork 7 hours ago.