Tobi Vail opened her diary. It was October 21, 1990, and the 21-year-old drummer set out to pen a Statement of Intent for her brand new punk rock band, Bikini Kill, the one that would fuel thirdwave feminism and create watershed moments. She had dreamt of starting a world-ruling all-girl band since her teen years. The writings in her zine, Jigsaw, archived last year at Harvard, helped steer what we know as the DIY punk-feminist movement, Riot Grrrl. Vail’s diary entry was likewise laced with ideology. She was philosophizing a future feminism by describing her own inquisitive evolution, politicizing punk by charging it with the conditions of her life as a woman. Bikini Kill, she wrote, would fight sexism and homophobia, legitimize girl-rock, reclaim the punk domain. For the time being, they ruled their own tiny universe. “I can already feel the power of it and the band is fast becoming the most important thing in my life,” Vail wrote. “I think we will be like thee most misunderstood band ever.” The truth of her vision would soon be revealed—loudly, with serious tunes, and music that was straight fire.

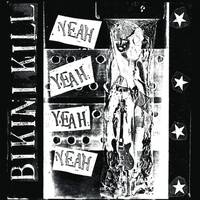

Tobi Vail opened her diary. It was October 21, 1990, and the 21-year-old drummer set out to pen a Statement of Intent for her brand new punk rock band, Bikini Kill, the one that would fuel thirdwave feminism and create watershed moments. She had dreamt of starting a world-ruling all-girl band since her teen years. The writings in her zine, Jigsaw, archived last year at Harvard, helped steer what we know as the DIY punk-feminist movement, Riot Grrrl. Vail’s diary entry was likewise laced with ideology. She was philosophizing a future feminism by describing her own inquisitive evolution, politicizing punk by charging it with the conditions of her life as a woman. Bikini Kill, she wrote, would fight sexism and homophobia, legitimize girl-rock, reclaim the punk domain. For the time being, they ruled their own tiny universe. “I can already feel the power of it and the band is fast becoming the most important thing in my life,” Vail wrote. “I think we will be like thee most misunderstood band ever.” The truth of her vision would soon be revealed—loudly, with serious tunes, and music that was straight fire.Yeah Yeah Yeah Yeah, out in March 1993, was their second record, a split with British riot grrrl spokespeople Huggy Bear. Bikini Kill’s half was tracked a year prior in the basement of D.C. punk house the Embassy, where they practiced, and released for their tour with Huggy Bear, which spawned a short doc titled literally: It Changed My Life. Yeah was more crudely recorded than the EP that preceded it, or the Joan Jett-produced “New Radio” single that followed, but these tightly-wound anthems and reprimands were the essence of early Bikini Kill. More than any formal Bikini Kill release, Yeah bears a proud and defiant aesthetic of lo-fi amateurism learned from Olympia’s K Records. The rage of their irreverent sneers and power chord slashes were explosive, and their presence was tough, pissed.

Bikini Kill followed a lineage of angry women in rock—the physical surge of X-Ray Spex, the gruff roar of Babes in Toyland. But no band actively created a counterculture for marginalized groups quite like them. To write protest songs that are as intellectually sharp as they are searingly cool and dryly witty—this is one of music culture’s enduring challenges, and Yeah remains a model of the form, a record with a cause and also real edge. The riffs were hard, the pace was breakneck, the drumming was anarchic, but Yeah was as hellishly catchy as it was raw. Kathleen Hanna, the trailblazing singer, said that in Bikini Kill she embodied 1,000 voices, and you can hear this on any of these songs. She pivots between radically contorted stylings—from a childish sing-song playground rhyme to a savage, lion’s roar—in order to show how things like masculinity and femininity were performed constructs, how those qualities are inside of us all. Despite these somewhat pointed concerns, Yeah rarely comes off as topical—Bikini Kill’s mantras are primarily inclusive and therefore timeless. Visceral empathy for the oppressed among us never goes out of style.

Hanna had a unique past, an artist and stripper who worked at a domestic violence shelter. Her mission was fueled with empirical evidence, which she clearly desired to share: Yeah’s opening sample finds a bro-moron suggesting that assault happens “because most of the girls ask for it.” The album is all fight songs, but “White Boy” takes no prisoners; it is pure opposition art, with Hanna appropriating a Rollins-like stalwart stance for her war. “I’m so sorry if I’m alienating some of you!” she screams, a mocking taunt. “Your whole fucking culture alienates me!” It is sad that this central line, a Bikini Kill thesis, feels pertinent in 2014—a world where hashtags must explain that rape culture exists (#RapeCultureIsWhen) and we struggle to eradicate the vicious prevalence of haphazard rape jokes. Hanna’s gritty missives used an uncomfortable erotics to illustrate imbalances of power ingrained everywhere. “It’s hard to talk with your dick in my mouth!” she wails. “I will try to scream in pain a little nicer next time!” The sarcasm is ruthless.

Bikini Kill’s early lyrics cut straight to the point, aphoristic truisms that worked as effectively in song as in the zine manifestos where they also appeared. The vocal escapades of “Don’t Need You” reject outward validation, and its anti-production aesthetic insures it. “This Is Not a Test” succinctly shows how society is flawed, not the girls that suffer because of it: a brutally grunted “YOU’RE FUCKED!” followed by an elastic, playful, and performative, “I’m naahhhht!” “Jigsaw Youth”, the fiery centerpiece, brings unity to their generation of grrrls, instilling the idea of a real social movement. But it underscores multiplicity therein—the many kinds of feminism, or the wide-open nature of riot grrrl. “We know there’s not one way/ One light/ One stupid truth!” Hanna shouts, a classic Bikini Kill line. “Don’t fit your definitions! Won’t meet your demands!” The subsequent track, “Resist Psychic Death”, drives the point that resisting definition (and, like, reading) is the punkest thing you can do.

The propulsive throb of “Rebel Girl” is Bikini Kill’s signature anthem and one of the most distinctive moments in American punk. Yeah marked the first release of this iconic song, a canonical rallying-call of female friendship and girl solidarity. “That girl thinks she’s the queen of the neighborhood!” Hanna shouts, signaling a floodgate of notes all coded with consciousness. “I’ve got news for you/ SHE IS!” This is spiritual music for feminist punks, yes, but also for outsiders of all stripes. The later Joan Jett-produced version broadened “Rebel Girl”s appeal—faster, tighter, slicker—but the sing-song chants and blurry-erotic “Uhhh”s here are animated, unnerving, provocative, showing cracks and nuance. Hanna’s nonconformist dream-grrrl steamrolled over female stereotypes in rock and the world, evoking revolution with every step.

The word “radical” should not be taken lightly here. This band aimed to fundamentally change how people thought about all manner of hierarchy. It also meant Bikini Kill would do things like climb the roof of a house screening “Twin Peaks”, disconnecting the antenna cable in order to sabotage the party. Bikini Kill were horrified by this show, which they felt had a sexist premise—the mystery of a beautiful dead girl. “We had a vendetta against ‘Twin Peaks’,” guitarist Billy Karren comically writes in the Yeah liner notes, offering context for their early track, “Fuck Twin Peaks”. It’s one of seven newly added early recordings that comprise Side B of this reissue—each purposefully added to illuminate something relevant about the band’s roots. “[‘Twin Peaks’] became the focal point of our initial anger in the band [laughs] which we thought was justified,” bassist Kathi Wilcox told Rookie.

The song highlights Bikini Kill’s biting sense of humor, no small feat in the realm of politicized music. As does “George Bush Is a Pig”, in which Karren grunts the title over a Sonic Youth-type freakout. The bloodcurdling shrieks of the Vail-sung “Not Right Now” prove, again, why she put the “grr” in “grrrl”, but its caterwauling rage is also terribly funny: “I’m not the kind of girl who’s gonna sit around and make you treats!” “I Busted in Your Chevy Window” is a powerful piece of spoken-word, performed live with terrifying, blood-boiling intensity, offering a tangible window into these legendary early shows. “Why”, Hanna writes in the notes, was her first go at songwriting, a piercing and raw ballad in the vein of her 1997 solo record Julie Ruin. The best of Side B is “Girl Soldier”, a chilling military march regarding the U.S. government’s ceaseless war on women—they used it to open a 1992 gig outside the Capitol with Fugazi, where they protested the rightward swing of the Supreme Court.

“I believe with my whole heartmindbody that girls constitute a revolutionary soul force that can, and will, change the world for real,” Hanna once wrote. It was only a matter of time. In 2011, before leading a guerrilla art collective that has effectively revealed the bitter truths of modern Russian life, Pussy Riot’s Nadya Tolokonnikova lectured at a conference on the history of feminist art; Bikini Kill was her first slide. In 2014, on the cover of the latest ELLE, teen publishing mogul Tavi Gevinson has interviewed pop’s reigning star, Miley Cyrus—discussing such topics as feminism and gender equality. Conversations in music have expanded and Bikini Kill and comrades pried them open. The dominant Y-chromosomes of punk’s DNA would not change on their own—the canon of Black Flag and Ramones, the degenerate gigs of macho-ritual where dudes went to get spat on. Imagine the air sucked from a room. The window has no handle. The door has no knob. The only option is to smash through and breathe. That was Bikini Kill, busting barriers in a way no one had. They staked out new territory in rock and now it belongs to them, and us. Reported by Pitchfork 13 minutes ago.