Three years ago, I found myself conducting a phone interview with Beck Hansen about 1960s French music, his disinterest audible over the line. But at the mention of the curious French chanteuse (as well as novelist, actress, playwright, and poet) Brigitte Fontaine and her decades-long musical collaboration with Kabyle musician Areski Belkacem, he noticeably brightened. That Hansen was a fan of the singular musical vision enacted by Fontaine and Belkacem was obvious, and in terms of 90s alt-rock icons, he was not alone: Fontaine’s oeuvre was a touchstone for the likes of Sonic Youth (Fontaine’s vocal affect and influence can clearly be heard in Kim Gordon’s songs), Björk, Jarvis Cocker, and Stereolab, to name but a few.

Three years ago, I found myself conducting a phone interview with Beck Hansen about 1960s French music, his disinterest audible over the line. But at the mention of the curious French chanteuse (as well as novelist, actress, playwright, and poet) Brigitte Fontaine and her decades-long musical collaboration with Kabyle musician Areski Belkacem, he noticeably brightened. That Hansen was a fan of the singular musical vision enacted by Fontaine and Belkacem was obvious, and in terms of 90s alt-rock icons, he was not alone: Fontaine’s oeuvre was a touchstone for the likes of Sonic Youth (Fontaine’s vocal affect and influence can clearly be heard in Kim Gordon’s songs), Björk, Jarvis Cocker, and Stereolab, to name but a few.And yet only with these recent reissues of Fontaine’s groundbreaking first two albums—1968’s Est…Folle and 1971’s Comme à La Radio—is her music domestically available in the US. By the time Fontaine made her recorded debut in 1968, she was already a published playwright and actress, appearing on numerous Parisian stages. Nearly 30 years of age by the time of the release of this debut album, Fontaine was a world away from French pop music’s stables of Yé-Yé girls, hewing slightly closer to the brooding chanson of Jacques Brel. Drawing on her experimental theatrical background, she began penning songs that abandoned standard pop rhyme schemes, using her artful pacing and a form of spoken word delivery that put her earthy, Marlene Dietrich intonation to the most effective use.

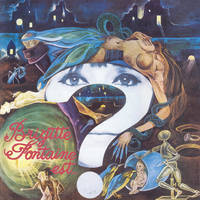

Within an album or two, Fontaine would be deep in avant-garde jazz and nascent world music hybrids, so in hindsight Est…Folle sounds the most traditional, even though it’s nothing of the sort—in fact, the title translates to “Brigitte Fontaine is crazy” and its cover features Fontaine’s striking dark eyes emanating from a big white question mark. Recorded in the studio with composer/arranger Jean-Claude Vannier—who would soon add orchestral heft to France’s greatest rock export, Serge Gainsbourg’s Histoire de Melody Nelson—Est…Folle is a playful, if ultimately misleading, debut.

Opener “Il Pleut” finds Fontaine in the most opulent orchestrations of her career, sounding like a precursor to Melody Nelson, Vannier applying garlands of strings and metallophones as a tympanum keeps the beat. “Le Beau Cancer” could be a jaunty number from the stage while “Je Suis Inadaptée” finds Fontaine's sultry voice sparring with woodwinds. Elsewhere, “Comme Rimbaud” speeds along on a peppy backbeat and frantic tambourines. The 11 songs that comprise Folle move with alacrity, with only two lasting longer than 3:30. Were it the lone album Fontaine ever recorded, it would be one of French pop’s more curious statements.

But as she began to work closer with proto-freak-folk/songwriter Jacques Higelin (he wrote one of Est…Folle’s songs) and her soon-to-be lifelong collaborator Areski Belkacem, her music mutated into something stranger and more wondrous. Comme à la Radio stems from the musical/theatrical works the three undertook at the end of the 1960s, where Fontaine’s husky spoken verses went atop spare and propulsive rhythms that drew on folk and Arabic and African instrumentation. The album’s coup comes in the form of Brigitte Fontaine and Areski bringing in the fiercely defiant jazz group the Art Ensemble of Chicago, who had decamped to Paris for a few years.

From the opening notes of that muscular walking bassline provided by Malachi Favors, the title track is a startling hybrid of avant-garde sensibilities—both of the free jazz and French rock variety—that entrances rather than excludes. The Art Ensemble could abstract and abandon structures with the best of American jazz ensembles of the late 60s, but here they play in the pocket to mesmerizing effect, from the lyrical horn lines provided by the frontline of Joseph Jarman, Roscoe Mitchell, and Leo Smith to the throbbing undertow provided by Favors and Belkacem, the rhythms foregrounded, the brass weaving in and around Fontaine’s seductive spoken lines for eight snake-charming minutes.

Or rather, her words only sound seductive to non-Francophone speakers, for Fontaine’s lyrics for “Comme à la Radio” comment on that acute sense of alienation and horror in the modern world, with lines about thousands weeping, police beating a young man, an alcoholic doctor, repeating a line that translates as “It’s cold in the world” in a whisper that sends shivers. Throughout the album, the Art Ensemble and Areski deploy hand percussion, bowed bass, bouzouki, shenai, sitar, lute, and muted brass to suggest Bedouin caravans, African tribal music, sub-Saharan buzzing, all of it beguiling and mysterious, feeling at once as if sounding from a great distance and via Fontaine’s hushed delivery, intimate.

The numbers featuring the Art Ensemble’s contributions remain some of free jazz’s most evocative crossovers, but what makes Comme a la Radio one of the era’s most striking documents is that even without the jazz musician guests, it’s a haunting acid-folk album underneath the brass. The album’s most stunning moments come when Areski handles all of the music around Fontaine’s vocals. There’s the ghostly shenai and bouzouki adding an exotic cast to the fragile incant of “L'Été L'Été”, or the strange strings on the harrowing album closer, “Lettre A Monsieur Le Chef De Gare De La Tour De Carol”, the sawed strings and buzzing drones—urged faster and faster by the hand drums and wordless vocals of Areski—build to a hypnotic and feverish climax. Both “Lettre” and the bonus track “Le Noir C'Est Mieux Choisi” remain some of the most beatific dark folk songs ever recorded, regardless of language. Reported by Pitchfork 9 hours ago.